Project Gutenberg's The Vision of Purgatory, Complete, by Dante Alighieri This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: The Vision of Purgatory, Complete Author: Dante Alighieri Release Date: August 5, 2004 [EBook #8795] Last Updated: July 21, 2014 Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE VISION OF PURGATORY, COMPLETE *** Produced by David Widger

Canto 1

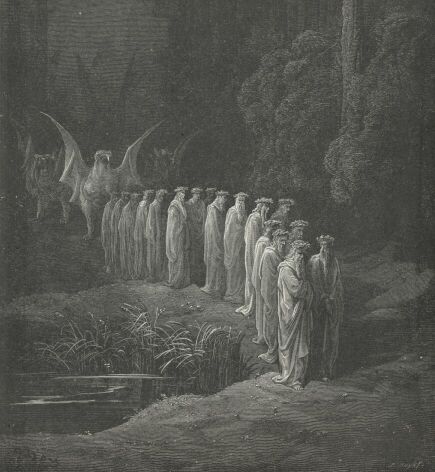

Canto 2

Canto 3

Canto 4

Canto 5

Canto 6

Canto 7

Canto 8

Canto 9

Canto 10

Canto 11

Canto 12

Canto 13

Canto 14

Canto 15

Canto 16

Canto 17

Canto 18

Canto 19

Canto 20

Canto 21

Canto 22

Canto 23

Canto 24

Canto 25

Canto 26

Canto 27

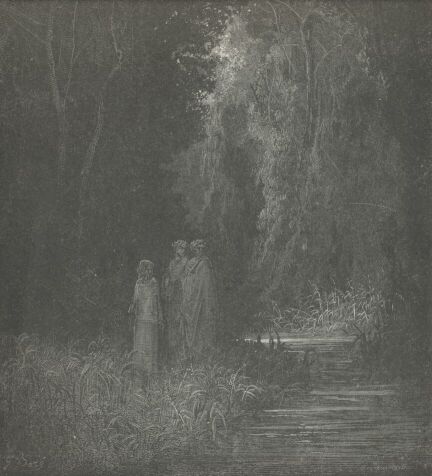

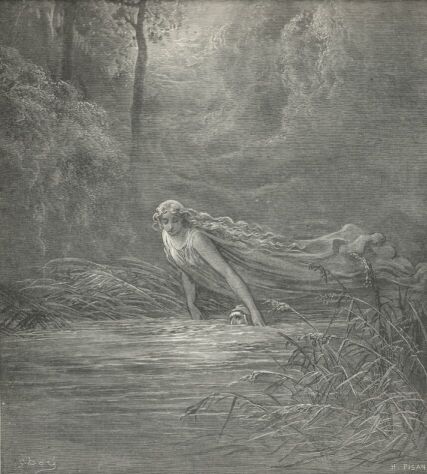

Canto 28

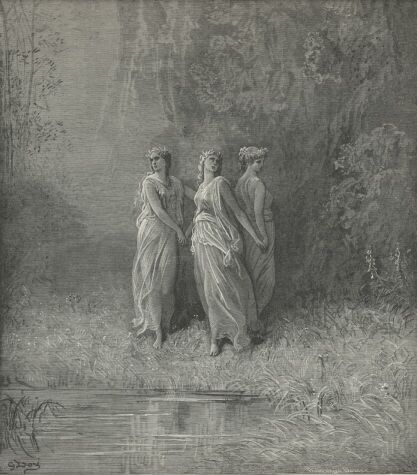

Canto 29

Canto 30

Canto 31

Canto 32

Canto 33

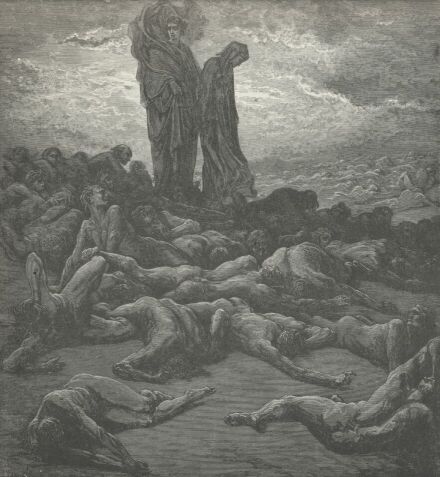

O'er better waves to speed her rapid course

The light bark of

my genius lifts the sail,

Well pleas'd to leave so cruel sea behind;

And of that second region will I sing,

In which the human spirit from

sinful blot

Is purg'd, and for ascent to Heaven prepares.

Here,

O ye hallow'd Nine! for in your train

I follow, here the deadened

strain revive;

Nor let Calliope refuse to sound

A somewhat

higher song, of that loud tone,

Which when the wretched birds of

chattering note

Had heard, they of forgiveness lost all hope.

Sweet hue of eastern sapphire, that was spread

O'er the serene

aspect of the pure air,

High up as the first circle, to mine eyes

Unwonted joy renew'd, soon as I 'scap'd

Forth from the atmosphere of

deadly gloom,

That had mine eyes and bosom fill'd with grief.

The radiant planet, that to love invites,

Made all the orient laugh,

and veil'd beneath

The Pisces' light, that in his escort came.

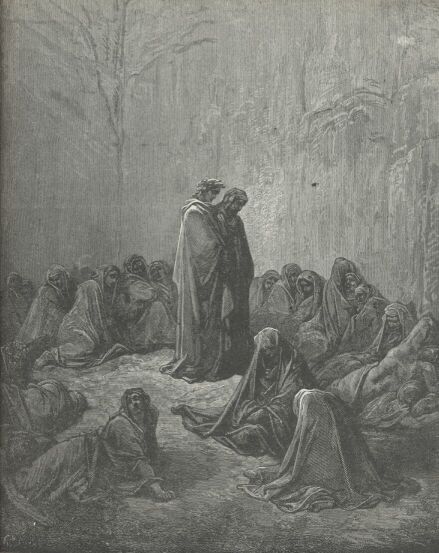

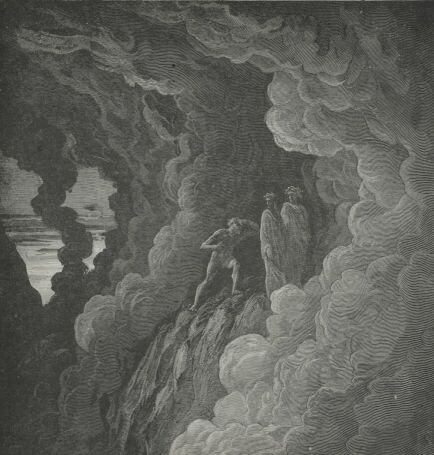

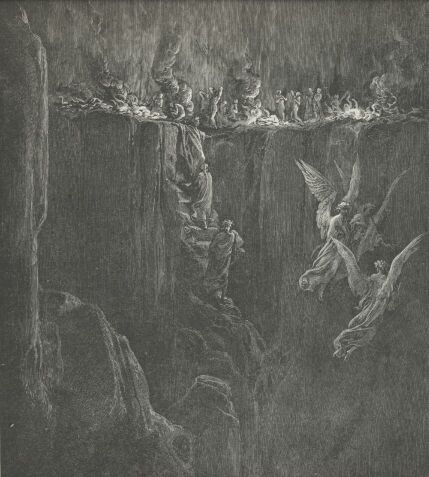

ENLARGE TO FULL SIZE

To the right hand I turn'd, and fix'd my mind

On the' other pole attentive, where I saw

Four stars ne'er seen

before save by the ken

Of our first parents. Heaven of their

rays

Seem'd joyous. O thou northern site, bereft

Indeed,

and widow'd, since of these depriv'd!

As from this view I had

desisted, straight

Turning a little tow'rds the other pole,

There from whence now the wain had disappear'd,

I saw an old man

standing by my side

Alone, so worthy of rev'rence in his look,

That ne'er from son to father more was ow'd.

Low down his beard and

mix'd with hoary white

Descended, like his locks, which parting fell

Upon his breast in double fold. The beams

Of those four

luminaries on his face

So brightly shone, and with such radiance

clear

Deck'd it, that I beheld him as the sun.

"Say who are

ye, that stemming the blind stream,

Forth from th' eternal

prison-house have fled?"

He spoke and moved those venerable plumes.

"Who hath conducted, or with lantern sure

Lights you emerging from

the depth of night,

That makes the infernal valley ever black?

Are the firm statutes of the dread abyss

Broken, or in high heaven

new laws ordain'd,

That thus, condemn'd, ye to my caves approach?"

ENLARGE TO FULL SIZE

My guide, then laying hold on me, by words

And intimations given with hand and head,

Made my bent knees and eye

submissive pay

Due reverence; then thus to him replied.

"Not

of myself I come; a Dame from heaven

Descending, had besought me in

my charge

To bring. But since thy will implies, that more

Our true condition I unfold at large,

Mine is not to deny thee thy

request.

This mortal ne'er hath seen the farthest gloom.

But

erring by his folly had approach'd

So near, that little space was

left to turn.

Then, as before I told, I was dispatch'd

To work

his rescue, and no way remain'd

Save this which I have ta'en. I

have display'd

Before him all the regions of the bad;

And

purpose now those spirits to display,

That under thy command are

purg'd from sin.

How I have brought him would be long to say.

From high descends the virtue, by whose aid

I to thy sight and

hearing him have led.

Now may our coming please thee. In the

search

Of liberty he journeys: that how dear

They know, who for

her sake have life refus'd.

Thou knowest, to whom death for her was

sweet

In Utica, where thou didst leave those weeds,

That in the

last great day will shine so bright.

For us the' eternal edicts are

unmov'd:

He breathes, and I am free of Minos' power,

Abiding in

that circle where the eyes

Of thy chaste Marcia beam, who still in

look

Prays thee, O hallow'd spirit! to own her shine.

Then by

her love we' implore thee, let us pass

Through thy sev'n regions; for

which best thanks

I for thy favour will to her return,

If

mention there below thou not disdain."

"Marcia so pleasing in my

sight was found,"

He then to him rejoin'd, "while I was there,

That all she ask'd me I was fain to grant.

Now that beyond the'

accursed stream she dwells,

She may no longer move me, by that law,

Which was ordain'd me, when I issued thence.

Not so, if Dame from

heaven, as thou sayst,

Moves and directs thee; then no flattery

needs.

Enough for me that in her name thou ask.

Go therefore

now: and with a slender reed

See that thou duly gird him, and his

face

Lave, till all sordid stain thou wipe from thence.

For not

with eye, by any cloud obscur'd,

Would it be seemly before him to

come,

Who stands the foremost minister in heaven.

This islet all

around, there far beneath,

Where the wave beats it, on the oozy bed

Produces store of reeds. No other plant,

Cover'd with leaves, or

harden'd in its stalk,

There lives, not bending to the water's sway.

After, this way return not; but the sun

Will show you, that now

rises, where to take

The mountain in its easiest ascent."

He

disappear'd; and I myself uprais'd

Speechless, and to my guide

retiring close,

Toward him turn'd mine eyes. He thus began;

"My son! observant thou my steps pursue.

We must retreat to rearward,

for that way

The champain to its low extreme declines."

The

dawn had chas'd the matin hour of prime,

Which deaf before it, so

that from afar

I spy'd the trembling of the ocean stream.

We

travers'd the deserted plain, as one

Who, wander'd from his track,

thinks every step

Trodden in vain till he regain the path.

When

we had come, where yet the tender dew

Strove with the sun, and in a

place, where fresh

The wind breath'd o'er it, while it slowly dried;

Both hands extended on the watery grass

My master plac'd, in graceful

act and kind.

Whence I of his intent before appriz'd,

Stretch'd

out to him my cheeks suffus'd with tears.

There to my visage he anew

restor'd

That hue, which the dun shades of hell conceal'd.

Then

on the solitary shore arriv'd,

That never sailing on its waters saw

Man, that could after measure back his course,

He girt me in such

manner as had pleas'd

Him who instructed, and O, strange to tell!

As he selected every humble plant,

Wherever one was pluck'd, another

there

Resembling, straightway in its place arose.

Now had the sun to that horizon reach'd,

That covers, with the

most exalted point

Of its meridian circle, Salem's walls,

And

night, that opposite to him her orb

Sounds, from the stream of Ganges

issued forth,

Holding the scales, that from her hands are dropp'd

When she reigns highest: so that where I was,

Aurora's white and

vermeil-tinctur'd cheek

To orange turn'd as she in age increas'd.

Meanwhile we linger'd by the water's brink,

Like men, who,

musing on their road, in thought

Journey, while motionless the body

rests.

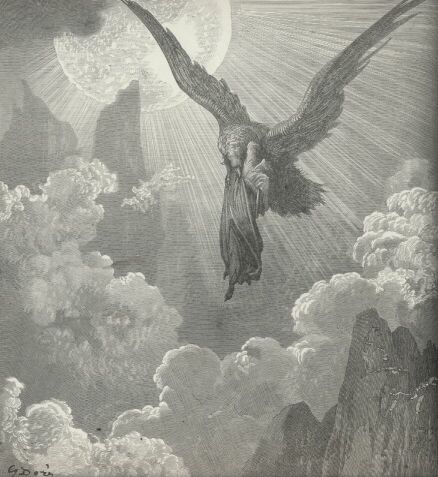

When lo! as near upon the hour of dawn,

Through the thick

vapours Mars with fiery beam

Glares down in west, over the ocean

floor;

So seem'd, what once again I hope to view,

A light so

swiftly coming through the sea,

No winged course might equal its

career.

From which when for a space I had withdrawn

Thine eyes,

to make inquiry of my guide,

Again I look'd and saw it grown in size

And brightness: thou on either side appear'd

Something, but what I

knew not of bright hue,

And by degrees from underneath it came

Another. My preceptor silent yet

Stood, while the brightness,

that we first discern'd,

Open'd the form of wings: then when he knew

The pilot, cried aloud, "Down, down; bend low

Thy knees; behold God's

angel: fold thy hands:

Now shalt thou see true Ministers indeed."

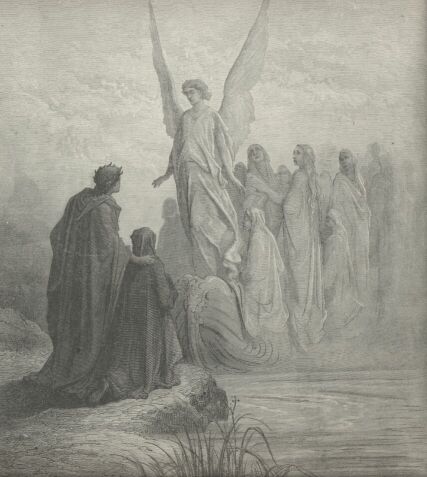

ENLARGE TO FULL SIZE

Lo how all human means he sets at naught!

So

that nor oar he needs, nor other sail

Except his wings, between such

distant shores.

Lo how straight up to heaven he holds them rear'd,

Winnowing the air with those eternal plumes,

That not like mortal

hairs fall off or change!"

As more and more toward us came, more

bright

Appear'd the bird of God, nor could the eye

Endure his

splendor near: I mine bent down.

He drove ashore in a small bark so

swift

And light, that in its course no wave it drank.

The

heav'nly steersman at the prow was seen,

Visibly written blessed in

his looks.

ENLARGE TO

FULL SIZE

Within a hundred spirits and more there sat.

"In

Exitu Israel de Aegypto;"

All with one voice together sang, with what

In the remainder of that hymn is writ.

Then soon as with the sign of

holy cross

He bless'd them, they at once leap'd out on land,

The

swiftly as he came return'd. The crew,

There left, appear'd astounded

with the place,

Gazing around as one who sees new sights.

From

every side the sun darted his beams,

And with his arrowy radiance

from mid heav'n

Had chas'd the Capricorn, when that strange tribe

Lifting their eyes towards us: "If ye know,

Declare what path will

Lead us to the mount."

Them Virgil answer'd. "Ye suppose

perchance

Us well acquainted with this place: but here,

We, as

yourselves, are strangers. Not long erst

We came, before you

but a little space,

By other road so rough and hard, that now

The' ascent will seem to us as play." The spirits,

Who from my

breathing had perceiv'd I liv'd,

Grew pale with wonder. As the

multitude

Flock round a herald, sent with olive branch,

To hear

what news he brings, and in their haste

Tread one another down, e'en

so at sight

Of me those happy spirits were fix'd, each one

Forgetful of its errand, to depart,

Where cleans'd from sin, it might

be made all fair.

Then one I saw darting before the rest

With such fond ardour to embrace me, I

To do the like was mov'd.

O shadows vain

Except in outward semblance! thrice my hands

I clasp'd behind it, they as oft return'd

Empty into my breast again.

Surprise

I needs must think was painted in my looks,

For

that the shadow smil'd and backward drew.

To follow it I hasten'd,

but with voice

Of sweetness it enjoin'd me to desist.

Then who

it was I knew, and pray'd of it,

To talk with me, it would a little

pause.

It answered: "Thee as in my mortal frame

I lov'd, so

loos'd forth it I love thee still,

And therefore pause; but why

walkest thou here?"

"Not without purpose once more to return,

Thou find'st me, my Casella, where I am

Journeying this way;" I said,

"but how of thee

Hath so much time been lost?" He answer'd

straight:

"No outrage hath been done to me, if he

Who when and

whom he chooses takes, me oft

This passage hath denied, since of just

will

His will he makes. These three months past indeed,

He, whose chose to enter, with free leave

Hath taken; whence I

wand'ring by the shore

Where Tyber's wave grows salt, of him gain'd

kind

Admittance, at that river's mouth, tow'rd which

His wings

are pointed, for there always throng

All such as not to Archeron

descend."

Then I: "If new laws have not quite destroy'd

Memory and use of that sweet song of love,

That while all my cares

had power to 'swage;

Please thee with it a little to console

My

spirit, that incumber'd with its frame,

Travelling so far, of pain is

overcome."

"Love that discourses in my thoughts." He then

Began in such soft accents, that within

The sweetness thrills me yet.

My gentle guide

And all who came with him, so well were

pleas'd,

That seem'd naught else might in their thoughts have room.

Fast fix'd in mute attention to his notes

We stood, when lo!

that old man venerable

Exclaiming, "How is this, ye tardy spirits?

What negligence detains you loit'ring here?

Run to the mountain to

cast off those scales,

That from your eyes the sight of God conceal."

As a wild flock of pigeons, to their food

Collected, blade or

tares, without their pride

Accustom'd, and in still and quiet sort,

If aught alarm them, suddenly desert

Their meal, assail'd by more

important care;

So I that new-come troop beheld, the song

Deserting, hasten to the mountain's side,

As one who goes yet where

he tends knows not.

Nor with less hurried step did we depart.

Them sudden flight had scatter'd over the plain,

Turn'd tow'rds

the mountain, whither reason's voice

Drives us; I to my faithful

company

Adhering, left it not. For how of him

Depriv'd,

might I have sped, or who beside

Would o'er the mountainous tract

have led my steps

He with the bitter pang of self-remorse

Seem'd

smitten. O clear conscience and upright

How doth a little fling

wound thee sore!

Soon as his feet desisted (slack'ning pace),

From haste, that mars all decency of act,

My mind, that in itself

before was wrapt,

Its thoughts expanded, as with joy restor'd:

And full against the steep ascent I set

My face, where highest to

heav'n its top o'erflows.

The sun, that flar'd behind, with

ruddy beam

Before my form was broken; for in me

His rays

resistance met. I turn'd aside

With fear of being left, when I

beheld

Only before myself the ground obscur'd.

When thus my

solace, turning him around,

Bespake me kindly: "Why distrustest thou?

Believ'st not I am with thee, thy sure guide?

It now is evening

there, where buried lies

The body, in which I cast a shade, remov'd

To Naples from Brundusium's wall. Nor thou

Marvel, if before me

no shadow fall,

More than that in the sky element

One ray

obstructs not other. To endure

Torments of heat and cold

extreme, like frames

That virtue hath dispos'd, which how it works

Wills not to us should be reveal'd. Insane

Who hopes, our

reason may that space explore,

Which holds three persons in one

substance knit.

Seek not the wherefore, race of human kind;

Could ye have seen the whole, no need had been

For Mary to bring

forth. Moreover ye

Have seen such men desiring fruitlessly;

To whose desires repose would have been giv'n,

That now but serve

them for eternal grief.

I speak of Plato, and the Stagyrite,

And

others many more." And then he bent

Downwards his forehead, and

in troubled mood

Broke off his speech. Meanwhile we had arriv'd

Far as the mountain's foot, and there the rock

Found of so steep

ascent, that nimblest steps

To climb it had been vain. The most

remote

Most wild untrodden path, in all the tract

'Twixt Lerice

and Turbia were to this

A ladder easy' and open of access.

"Who

knows on which hand now the steep declines?"

My master said and

paus'd, "so that he may

Ascend, who journeys without aid of wine?"

And while with looks directed to the ground

The meaning of the

pathway he explor'd,

And I gaz'd upward round the stony height,

Of spirits, that toward us mov'd their steps,

Yet moving seem'd not,

they so slow approach'd.

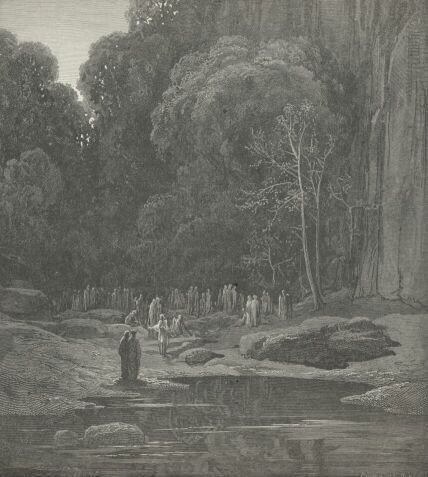

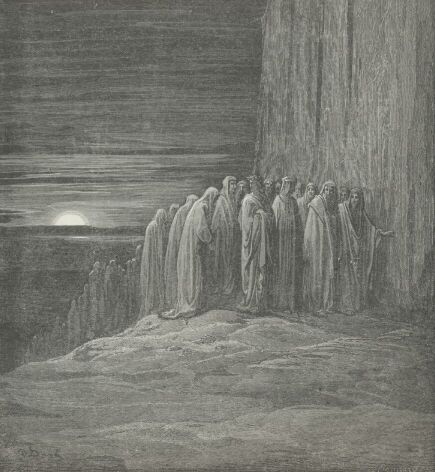

ENLARGE TO FULL SIZE

I thus my guide address'd: "Upraise thine eyes,

Lo that way some, of whom thou may'st obtain

Counsel, if of thyself

thou find'st it not!"

Straightway he look'd, and with free

speech replied:

"Let us tend thither: they but softly come.

And

thou be firm in hope, my son belov'd."

Now was that people

distant far in space

A thousand paces behind ours, as much

As at

a throw the nervous arm could fling,

When all drew backward on the

messy crags

Of the steep bank, and firmly stood unmov'd

As one

who walks in doubt might stand to look.

"O spirits perfect! O

already chosen!"

Virgil to them began, "by that blest peace,

Which, as I deem, is for you all prepar'd,

Instruct us where the

mountain low declines,

So that attempt to mount it be not vain.

For who knows most, him loss of time most grieves."

As sheep,

that step from forth their fold, by one,

Or pairs, or three at once;

meanwhile the rest

Stand fearfully, bending the eye and nose

To

ground, and what the foremost does, that do

The others, gath'ring

round her, if she stops,

Simple and quiet, nor the cause discern;

So saw I moving to advance the first,

Who of that fortunate crew were

at the head,

Of modest mien and graceful in their gait.

When

they before me had beheld the light

From my right side fall broken on

the ground,

So that the shadow reach'd the cave, they stopp'd

And somewhat back retir'd: the same did all,

Who follow'd, though

unweeting of the cause.

"Unask'd of you, yet freely I confess,

This is a human body which ye see.

That the sun's light is broken on

the ground,

Marvel not: but believe, that not without

Virtue

deriv'd from Heaven, we to climb

Over this wall aspire." So

them bespake

My master; and that virtuous tribe rejoin'd;

"Turn,

and before you there the entrance lies,"

Making a signal to us with

bent hands.

Then of them one began. "Whoe'er thou art,

Who journey'st thus this way, thy visage turn,

Think if me elsewhere

thou hast ever seen."

I tow'rds him turn'd, and with fix'd eye

beheld.

Comely, and fair, and gentle of aspect,

He seem'd, but

on one brow a gash was mark'd.

When humbly I disclaim'd to have

beheld

Him ever: "Now behold!" he said, and show'd

High on

his breast a wound: then smiling spake.

"I am Manfredi, grandson

to the Queen

Costanza: whence I pray thee, when return'd,

To my

fair daughter go, the parent glad

Of Aragonia and Sicilia's pride;

And of the truth inform her, if of me

Aught else be told. When

by two mortal blows

My frame was shatter'd, I betook myself

Weeping to him, who of free will forgives.

My sins were horrible; but

so wide arms

Hath goodness infinite, that it receives

All who

turn to it. Had this text divine

Been of Cosenza's shepherd

better scann'd,

Who then by Clement on my hunt was set,

Yet at

the bridge's head my bones had lain,

Near Benevento, by the heavy

mole

Protected; but the rain now drenches them,

And the wind

drives, out of the kingdom's bounds,

Far as the stream of Verde,

where, with lights

Extinguish'd, he remov'd them from their bed.

Yet by their curse we are not so destroy'd,

But that the eternal love

may turn, while hope

Retains her verdant blossoms. True it is,

That such one as in contumacy dies

Against the holy church, though he

repent,

Must wander thirty-fold for all the time

In his

presumption past; if such decree

Be not by prayers of good men

shorter made

Look therefore if thou canst advance my bliss;

Revealing to my good Costanza, how

Thou hast beheld me, and beside

the terms

Laid on me of that interdict; for here

By means of

those below much profit comes."

When by sensations of delight or pain,

That any of our

faculties hath seiz'd,

Entire the soul collects herself, it seems

She is intent upon that power alone,

And thus the error is disprov'd

which holds

The soul not singly lighted in the breast.

And

therefore when as aught is heard or seen,

That firmly keeps the soul

toward it turn'd,

Time passes, and a man perceives it not.

For

that, whereby he hearken, is one power,

Another that, which the whole

spirit hash;

This is as it were bound, while that is free.

This

found I true by proof, hearing that spirit

And wond'ring; for full

fifty steps aloft

The sun had measur'd unobserv'd of me,

When we

arriv'd where all with one accord

The spirits shouted, "Here is what

ye ask."

A larger aperture ofttimes is stopp'd

With forked

stake of thorn by villager,

When the ripe grape imbrowns, than was

the path,

By which my guide, and I behind him close,

Ascended

solitary, when that troop

Departing left us. On Sanleo's road

Who journeys, or to Noli low descends,

Or mounts Bismantua's height,

must use his feet;

But here a man had need to fly, I mean

With

the swift wing and plumes of high desire,

Conducted by his aid, who

gave me hope,

And with light furnish'd to direct my way.

ENLARGE TO FULL SIZE

We through the broken rock ascended, close

Pent on each side, while underneath the ground

Ask'd help of hands

and feet. When we arriv'd

Near on the highest ridge of the

steep bank,

Where the plain level open'd I exclaim'd,

"O master!

say which way can we proceed?"

He answer'd, "Let no step of

thine recede.

Behind me gain the mountain, till to us

Some

practis'd guide appear." That eminence

Was lofty that no eye

might reach its point,

And the side proudly rising, more than line

From the mid quadrant to the centre drawn.

I wearied thus began:

"Parent belov'd!

Turn, and behold how I remain alone,

If thou

stay not."—"My son!" He straight reply'd,

"Thus far put

forth thy strength;" and to a track

Pointed, that, on this side

projecting, round

Circles the hill. His words so spurr'd me on,

That I behind him clamb'ring, forc'd myself,

Till my feet press'd the

circuit plain beneath.

There both together seated, turn'd we round

To eastward, whence was our ascent: and oft

Many beside have with

delight look'd back.

First on the nether shores I turn'd my

eyes,

Then rais'd them to the sun, and wond'ring mark'd

That

from the left it smote us. Soon perceiv'd

That Poet sage now at

the car of light

Amaz'd I stood, where 'twixt us and the north

Its course it enter'd. Whence he thus to me:

"Were Leda's

offspring now in company

Of that broad mirror, that high up and low

Imparts his light beneath, thou might'st behold

The ruddy zodiac

nearer to the bears

Wheel, if its ancient course it not forsook.

How that may be if thou would'st think; within

Pond'ring, imagine

Sion with this mount

Plac'd on the earth, so that to both be one

Horizon, and two hemispheres apart,

Where lies the path that Phaeton

ill knew

To guide his erring chariot: thou wilt see

How of

necessity by this on one

He passes, while by that on the' other side,

If with clear view shine intellect attend."

"Of truth, kind

teacher!" I exclaim'd, "so clear

Aught saw I never, as I now

discern

Where seem'd my ken to fail, that the mid orb

Of the

supernal motion (which in terms

Of art is called the Equator, and

remains

Ever between the sun and winter) for the cause

Thou hast

assign'd, from hence toward the north

Departs, when those who in the

Hebrew land

Inhabit, see it tow'rds the warmer part.

But if it

please thee, I would gladly know,

How far we have to journey: for the

hill

Mounts higher, than this sight of mine can mount."

He

thus to me: "Such is this steep ascent,

That it is ever difficult at

first,

But, more a man proceeds, less evil grows.

When pleasant

it shall seem to thee, so much

That upward going shall be easy to

thee.

As in a vessel to go down the tide,

Then of this path thou

wilt have reach'd the end.

There hope to rest thee from thy toil.

No more

I answer, and thus far for certain know."

As he

his words had spoken, near to us

A voice there sounded: "Yet ye first

perchance

May to repose you by constraint be led."

At sound

thereof each turn'd, and on the left

A huge stone we beheld, of which

nor I

Nor he before was ware. Thither we drew,

find there

were some, who in the shady place

Behind the rock were standing, as a

man

Thru' idleness might stand. Among them one,

Who seem'd

to me much wearied, sat him down,

And with his arms did fold his

knees about,

Holding his face between them downward bent.

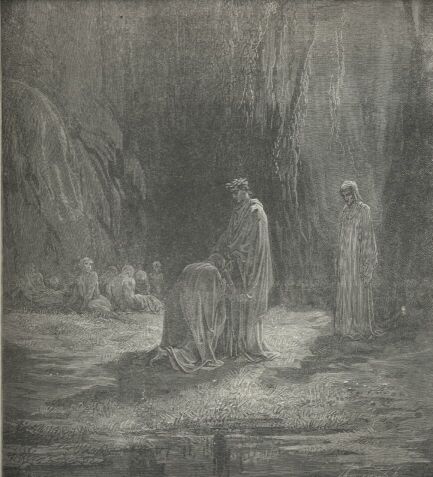

ENLARGE TO FULL SIZE

"Sweet Sir!" I cry'd, "behold that man,

who shows

Himself more idle, than if laziness

Were sister to

him." Straight he turn'd to us,

And, o'er the thigh lifting his

face, observ'd,

Then in these accents spake: "Up then, proceed

Thou valiant one." Straight who it was I knew;

Nor could the

pain I felt (for want of breath

Still somewhat urg'd me) hinder my

approach.

And when I came to him, he scarce his head

Uplifted,

saying "Well hast thou discern'd,

How from the left the sun his

chariot leads."

His lazy acts and broken words my lips

To

laughter somewhat mov'd; when I began:

"Belacqua, now for thee I

grieve no more.

But tell, why thou art seated upright there?

Waitest thou escort to conduct thee hence?

Or blame I only shine

accustom'd ways?"

Then he: "My brother, of what use to mount,

When to my suffering would not let me pass

The bird of God, who at

the portal sits?

Behooves so long that heav'n first bear me round

Without its limits, as in life it bore,

Because I to the end

repentant Sighs

Delay'd, if prayer do not aid me first,

That

riseth up from heart which lives in grace.

What other kind avails,

not heard in heaven?"'

Before me now the Poet up the mount

Ascending, cried: "Haste thee, for see the sun

Has touch'd the point

meridian, and the night

Now covers with her foot Marocco's shore."

Now had I left those spirits, and pursued

The steps of my

Conductor, when beheld

Pointing the finger at me one exclaim'd:

"See how it seems as if the light not shone

From the left hand of him

beneath, and he,

As living, seems to be led on." Mine eyes

I at that sound reverting, saw them gaze

Through wonder first at me,

and then at me

And the light broken underneath, by turns.

"Why

are thy thoughts thus riveted?" my guide

Exclaim'd, "that thou

hast slack'd thy pace? or how

Imports it thee, what thing is

whisper'd here?

Come after me, and to their babblings leave

The

crowd. Be as a tower, that, firmly set,

Shakes not its top for any

blast that blows!

He, in whose bosom thought on thought shoots out,

Still of his aim is wide, in that the one

Sicklies and wastes to

nought the other's strength."

What

other could I answer save "I come?"

I said it, somewhat with that

colour ting'd

Which ofttimes pardon meriteth for man.

Meanwhile

traverse along the hill there came,

A little way before us, some who

sang

The "Miserere" in responsive Strains.

When they perceiv'd

that through my body I

Gave way not for the rays to pass, their song

Straight to a long and hoarse exclaim they chang'd;

And two of them,

in guise of messengers,

Ran on to meet us, and inquiring ask'd:

"Of your condition we would gladly learn."

To

them my guide. "Ye may return, and bear

Tidings to them who

sent you, that his frame

Is real flesh. If, as I deem, to view

His shade they paus'd, enough is answer'd them.

Him let them honour,

they may prize him well."

Ne'er saw I

fiery vapours with such speed

Cut through the serene air at fall of

night,

Nor August's clouds athwart the setting sun,

That upward

these did not in shorter space

Return; and, there arriving, with the

rest

Wheel back on us, as with loose rein a troop.

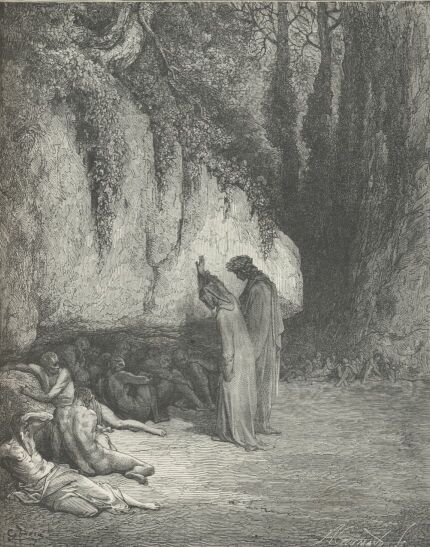

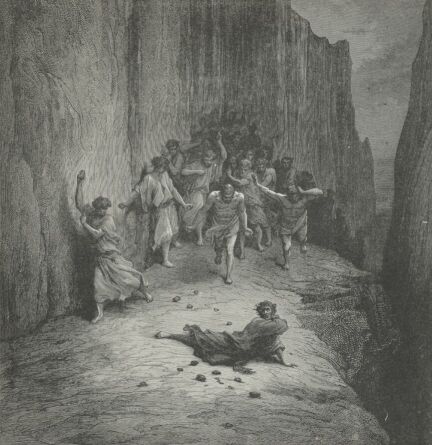

ENLARGE TO FULL SIZE

"Many," exclaim'd the

bard, "are these, who throng

Around us: to petition thee they come.

Go therefore on, and listen as thou go'st."

"O

spirit! who go'st on to blessedness

With the same limbs, that clad

thee at thy birth."

Shouting they came, "a little rest thy step.

Look if thou any one amongst our tribe

Hast e'er beheld, that tidings

of him there

Thou mayst report. Ah, wherefore go'st thou on?

Ah wherefore tarriest thou not? We all

By violence died, and to

our latest hour

Were sinners, but then warn'd by light from heav'n,

So that, repenting and forgiving, we

Did issue out of life at peace

with God,

Who with desire to see him fills our heart."

Then

I: "The visages of all I scan

Yet none of ye remember. But if

aught,

That I can do, may please you, gentle spirits!

Speak; and

I will perform it, by that peace,

Which on the steps of guide so

excellent

Following from world to world intent I seek."

In

answer he began: "None here distrusts

Thy kindness, though not

promis'd with an oath;

So as the will fail not for want of power.

Whence I, who sole before the others speak,

Entreat thee, if thou

ever see that land,

Which lies between Romagna and the realm

Of

Charles, that of thy courtesy thou pray

Those who inhabit Fano, that

for me

Their adorations duly be put up,

By which I may purge off

my grievous sins.

From thence I came. But the deep passages,

Whence issued out the blood wherein I dwelt,

Upon my bosom in

Antenor's land

Were made, where to be more secure I thought.

The

author of the deed was Este's prince,

Who, more than right could

warrant, with his wrath

Pursued me. Had I towards Mira fled,

When overta'en at Oriaco, still

Might I have breath'd. But to the

marsh I sped,

And in the mire and rushes tangled there

Fell, and

beheld my life-blood float the plain."

Then

said another: "Ah! so may the wish,

That takes thee o'er the

mountain, be fulfill'd,

As thou shalt graciously give aid to mine.

Of Montefeltro I; Buonconte I:

Giovanna nor none else have care for

me,

Sorrowing with these I therefore go." I thus:

"From

Campaldino's field what force or chance

Drew thee, that ne'er thy

sepulture was known?"

"Oh!" answer'd

he, "at Casentino's foot

A stream there courseth, nam'd Archiano,

sprung

In Apennine above the Hermit's seat.

E'en where its name

is cancel'd, there came I,

Pierc'd in the heart, fleeing away on

foot,

And bloodying the plain. Here sight and speech

Fail'd me, and finishing with Mary's name

I fell, and tenantless my

flesh remain'd.

I will report the truth; which thou again

Tell

to the living. Me God's angel took,

Whilst he of hell

exclaim'd: "O thou from heav'n!

Say wherefore hast thou robb'd me?

Thou of him

Th' eternal portion bear'st with thee away

For

one poor tear that he deprives me of.

But of the other, other rule I

make."

"Thou knowest how in the

atmosphere collects

That vapour dank, returning into water,

Soon

as it mounts where cold condenses it.

That evil will, which in his

intellect

Still follows evil, came, and rais'd the wind

And

smoky mist, by virtue of the power

Given by his nature. Thence

the valley, soon

As day was spent, he cover'd o'er with cloud

From Pratomagno to the mountain range,

And stretch'd the sky above,

so that the air

Impregnate chang'd to water. Fell the rain,

And to the fosses came all that the land

Contain'd not; and, as

mightiest streams are wont,

To the great river with such headlong

sweep

Rush'd, that nought stay'd its course. My stiffen'd frame

Laid at his mouth the fell Archiano found,

And dash'd it into Arno,

from my breast

Loos'ning the cross, that of myself I made

When

overcome with pain. He hurl'd me on,

Along the banks and bottom

of his course;

Then in his muddy spoils encircling wrapt."

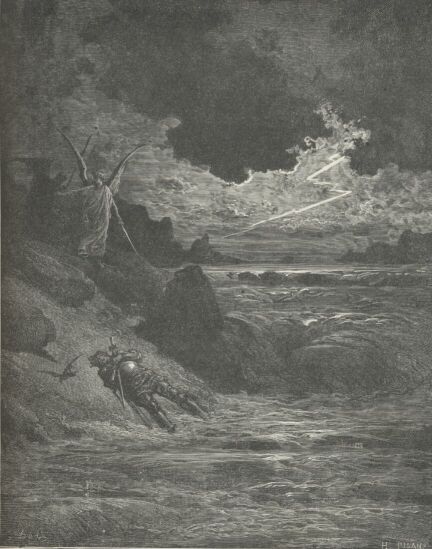

ENLARGE TO FULL SIZE

"Ah! when thou to the

world shalt be return'd,

And rested after thy long road," so spake

Next the third spirit; "then remember me.

I once was Pia. Sienna

gave me life,

Maremma took it from me. That he knows,

Who

me with jewell'd ring had first espous'd."

ENLARGE TO FULL SIZE

When from their game of dice men separate,

He, who hath lost,

remains in sadness fix'd,

Revolving in his mind, what luckless throws

He cast: but meanwhile all the company

Go with the other; one before

him runs,

And one behind his mantle twitches, one

Fast by his

side bids him remember him.

He stops not; and each one, to whom his

hand

Is stretch'd, well knows he bids him stand aside;

And thus

he from the press defends himself.

E'en such was I in that

close-crowding throng;

And turning so my face around to all,

And

promising, I 'scap'd from it with pains.

Here

of Arezzo him I saw, who fell

By Ghino's cruel arm; and him beside,

Who in his chase was swallow'd by the stream.

Here Frederic Novello,

with his hand

Stretch'd forth, entreated; and of Pisa he,

Who

put the good Marzuco to such proof

Of constancy. Count Orso I

beheld;

And from its frame a soul dismiss'd for spite

And envy,

as it said, but for no crime:

I speak of Peter de la Brosse; and

here,

While she yet lives, that Lady of Brabant

Let her beware;

lest for so false a deed

She herd with worse than these. When I was

freed

From all those spirits, who pray'd for others' prayers

To

hasten on their state of blessedness;

Straight I began: "O thou, my

luminary!

It seems expressly in thy text denied,

That heaven's

supreme decree can never bend

To supplication; yet with this design

Do these entreat. Can then their hope be vain,

Or is thy saying

not to me reveal'd?"

He thus to me:

"Both what I write is plain,

And these deceiv'd not in their hope, if

well

Thy mind consider, that the sacred height

Of judgment doth

not stoop, because love's flame

In a short moment all fulfils, which

he

Who sojourns here, in right should satisfy.

Besides, when I

this point concluded thus,

By praying no defect could be supplied;

Because the pray'r had none access to God.

Yet in this deep suspicion

rest thou not

Contented unless she assure thee so,

Who betwixt

truth and mind infuses light.

I know not if thou take me right; I

mean

Beatrice. Her thou shalt behold above,

Upon this

mountain's crown, fair seat of joy."

Then

I: "Sir! let us mend our speed; for now

I tire not as before; and lo!

the hill

Stretches its shadow far." He answer'd thus:

"Our

progress with this day shall be as much

As we may now dispatch; but

otherwise

Than thou supposest is the truth. For there

Thou

canst not be, ere thou once more behold

Him back returning, who

behind the steep

Is now so hidden, that as erst his beam

Thou

dost not break. But lo! a spirit there

Stands solitary, and

toward us looks:

It will instruct us in the speediest way."

We soon approach'd it. O thou Lombard

spirit!

How didst thou stand, in high abstracted mood,

Scarce

moving with slow dignity thine eyes!

It spoke not aught, but let us

onward pass,

Eyeing us as a lion on his watch.

But Virgil with

entreaty mild advanc'd,

Requesting it to show the best ascent.

It answer to his question none return'd,

But of our country and our

kind of life

Demanded. When my courteous guide began,

"Mantua," the solitary shadow quick

Rose towards us from the place in

which it stood,

And cry'd, "Mantuan! I am thy countryman

Sordello." Each the other then embrac'd.

Ah

slavish Italy! thou inn of grief,

Vessel without a pilot in loud

storm,

Lady no longer of fair provinces,

But brothel-house

impure! this gentle spirit,

Ev'n from the Pleasant sound of his dear

land

Was prompt to greet a fellow citizen

With such glad cheer;

while now thy living ones

In thee abide not without war; and one

Malicious gnaws another, ay of those

Whom the same wall and the same

moat contains,

Seek, wretched one! around thy sea-coasts wide;

Then homeward to thy bosom turn, and mark

If any part of the sweet

peace enjoy.

What boots it, that thy reins Justinian's hand

Befitted, if thy saddle be unpress'd?

Nought doth he now but

aggravate thy shame.

Ah people! thou obedient still shouldst live,

And in the saddle let thy Caesar sit,

If well thou marked'st that

which God commands.

Look how that beast

to felness hath relaps'd

From having lost correction of the spur,

Since to the bridle thou hast set thine hand,

O German Albert! who

abandon'st her,

That is grown savage and unmanageable,

When thou

should'st clasp her flanks with forked heels.

Just judgment from the

stars fall on thy blood!

And be it strange and manifest to all!

Such as may strike thy successor with dread!

For that thy sire and

thou have suffer'd thus,

Through greediness of yonder realms

detain'd,

The garden of the empire to run waste.

Come see the

Capulets and Montagues,

The Philippeschi and Monaldi! man

Who

car'st for nought! those sunk in grief, and these

With dire suspicion

rack'd. Come, cruel one!

Come and behold the' oppression of the

nobles,

And mark their injuries: and thou mayst see.

What safety

Santafiore can supply.

Come and behold thy Rome, who calls on thee,

Desolate widow! day and night with moans:

"My Caesar, why dost thou

desert my side?"

Come and behold what love among thy people:

And

if no pity touches thee for us,

Come and blush for thine own report.

For me,

If it be lawful, O Almighty Power,

Who wast in

earth for our sakes crucified!

Are thy just eyes turn'd elsewhere?

or is this

A preparation in the wond'rous depth

Of thy

sage counsel made, for some good end,

Entirely from our reach of

thought cut off?

So are the' Italian cities all o'erthrong'd

With tyrants, and a great Marcellus made

Of every petty factious

villager.

My Florence! thou mayst well

remain unmov'd

At this digression, which affects not thee:

Thanks to thy people, who so wisely speed.

Many have justice in their

heart, that long

Waiteth for counsel to direct the bow,

Or ere

it dart unto its aim: but shine

Have it on their lip's edge. Many

refuse

To bear the common burdens: readier thine

Answer

uneall'd, and cry, "Behold I stoop!"

Make

thyself glad, for thou hast reason now,

Thou wealthy! thou at peace!

thou wisdom-fraught!

Facts best witness if I speak the truth.

Athens and Lacedaemon, who of old

Enacted laws, for civil arts

renown'd,

Made little progress in improving life

Tow'rds thee,

who usest such nice subtlety,

That to the middle of November scarce

Reaches the thread thou in October weav'st.

How many times, within

thy memory,

Customs, and laws, and coins, and offices

Have been

by thee renew'd, and people chang'd!

If

thou remember'st well and can'st see clear,

Thou wilt perceive

thyself like a sick wretch,

Who finds no rest upon her down, but oft

Shifting her side, short respite seeks from pain.

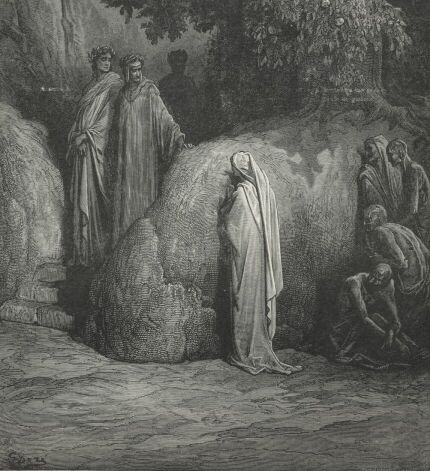

After their courteous greetings joyfully

Sev'n times exchang'd,

Sordello backward drew

Exclaiming, "Who are ye?" "Before this

mount

By spirits worthy of ascent to God

Was sought, my bones

had by Octavius' care

Been buried. I am Virgil, for no sin

Depriv'd of heav'n, except for lack of faith."

So

answer'd him in few my gentle guide.

As

one, who aught before him suddenly

Beholding, whence his wonder

riseth, cries

"It is yet is not," wav'ring in belief;

Such he

appear'd; then downward bent his eyes,

And drawing near with

reverential step,

Caught him, where of mean estate might clasp

His lord. "Glory of Latium!" he exclaim'd,

"In whom our tongue

its utmost power display'd!

Boast of my honor'd birth-place! what

desert

Of mine, what favour rather undeserv'd,

Shows thee to me?

If I to hear that voice

Am worthy, say if from below thou

com'st

And from what cloister's pale?"—"Through every orb

Of that sad region," he reply'd, "thus far

Am I arriv'd, by heav'nly

influence led

And with such aid I come. There is a place

There underneath, not made by torments sad,

But by dun shades alone;

where mourning's voice

Sounds not of anguish sharp, but breathes in

sighs."

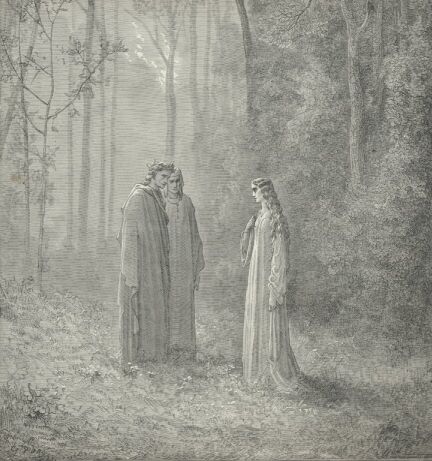

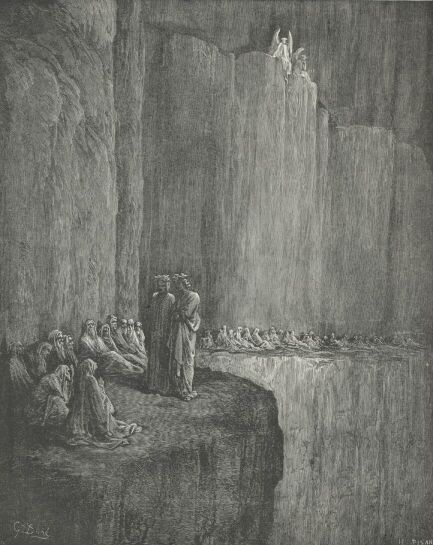

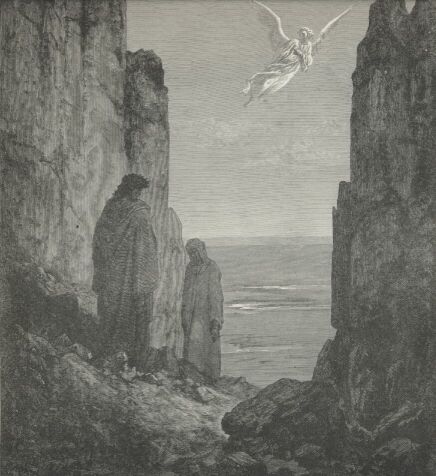

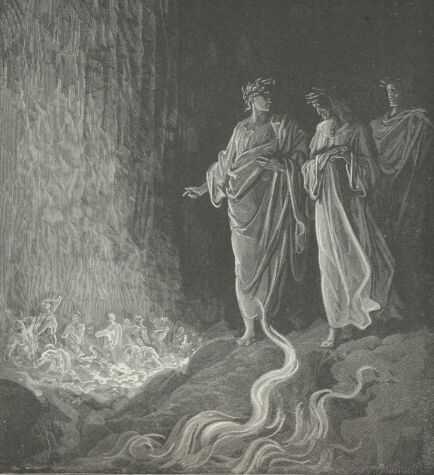

ENLARGE TO

FULL SIZE

There I with little innocents abide,

Who by

death's fangs were bitten, ere exempt

From human taint. There I

with those abide,

Who the three holy virtues put not on,

But

understood the rest, and without blame

Follow'd them all. But

if thou know'st and canst,

Direct us, how we soonest may arrive,

Where Purgatory its true beginning takes."

He

answer'd thus: "We have no certain place

Assign'd us: upwards I may

go or round,

Far as I can, I join thee for thy guide.

But thou

beholdest now how day declines:

And upwards to proceed by night, our

power

Excels: therefore it may be well to choose

A place of

pleasant sojourn. To the right

Some spirits sit apart retir'd.

If thou

Consentest, I to these will lead thy steps:

And

thou wilt know them, not without delight."

"How

chances this?" was answer'd; "who so wish'd

To ascend by night,

would he be thence debarr'd

By other, or through his own weakness

fail?"

The good Sordello then, along

the ground

Trailing his finger, spoke: "Only this line

Thou

shalt not overpass, soon as the sun

Hath disappear'd; not that aught

else impedes

Thy going upwards, save the shades of night.

These

with the wont of power perplex the will.

With them thou haply mightst

return beneath,

Or to and fro around the mountain's side

Wander,

while day is in the horizon shut."

My

master straight, as wond'ring at his speech,

Exclaim'd: "Then lead us

quickly, where thou sayst,

That, while we stay, we may enjoy

delight."

A little space we were

remov'd from thence,

When I perceiv'd the mountain hollow'd out.

Ev'n as large valleys hollow'd out on earth,

"That

way," the' escorting spirit cried, "we go,

Where in a bosom the high

bank recedes:

And thou await renewal of the day."

Betwixt

the steep and plain a crooked path

Led us traverse into the ridge's

side,

Where more than half the sloping edge expires.

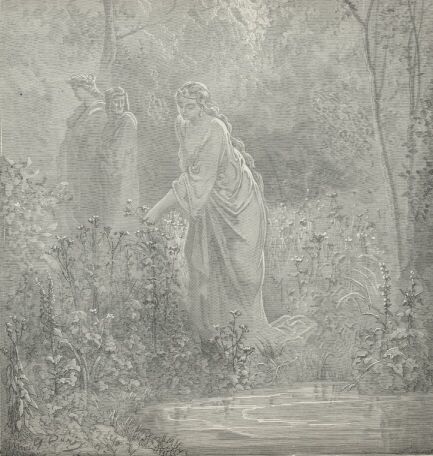

Refulgent

gold, and silver thrice refin'd,

And scarlet grain and ceruse, Indian

wood

Of lucid dye serene, fresh emeralds

But newly broken, by

the herbs and flowers

Plac'd in that fair recess, in color all

Had been surpass'd, as great surpasses less.

Nor nature only there

lavish'd her hues,

But of the sweetness of a thousand smells

A

rare and undistinguish'd fragrance made.

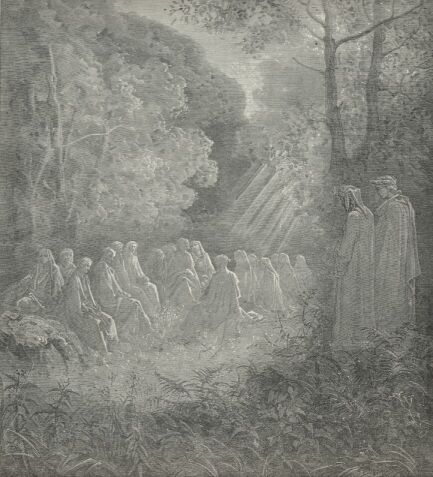

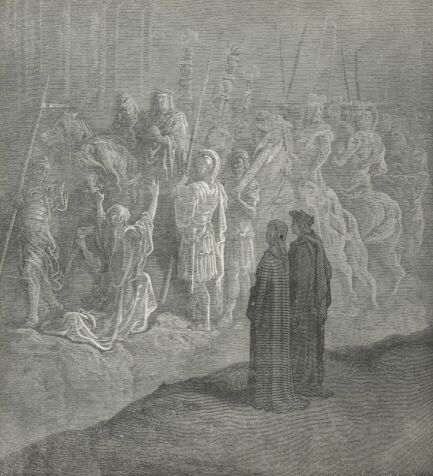

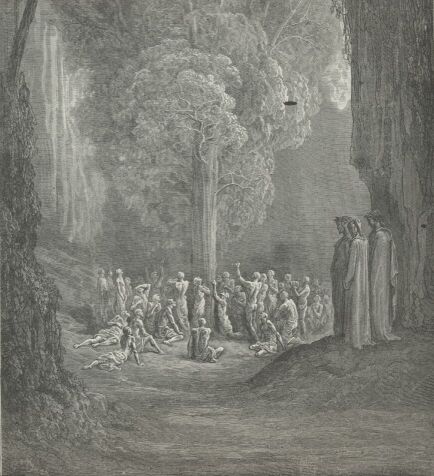

ENLARGE TO FULL SIZE

"Salve Regina," on the

grass and flowers

Here chanting I beheld those spirits sit

Who

not beyond the valley could be seen.

"Before

the west'ring sun sink to his bed,"

Began the Mantuan, who our steps

had turn'd,

"'Mid those desires not

that I lead ye on.

For from this eminence ye shall discern

Better the acts and visages of all,

Than in the nether vale among

them mix'd.

He, who sits high above the rest, and seems

To have

neglected that he should have done,

And to the others' song moves not

his lip,

The Emperor Rodolph call, who might have heal'd

The

wounds whereof fair Italy hath died,

So that by others she revives

but slowly,

He, who with kindly visage comforts him,

Sway'd in

that country, where the water springs,

That Moldaw's river to the

Elbe, and Elbe

Rolls to the ocean: Ottocar his name:

Who in his

swaddling clothes was of more worth

Than Winceslaus his son, a

bearded man,

Pamper'd with rank luxuriousness and ease.

And that

one with the nose depress, who close

In counsel seems with him of

gentle look,

Flying expir'd, with'ring the lily's flower.

Look

there how he doth knock against his breast!

The other ye behold, who

for his cheek

Makes of one hand a couch, with frequent sighs.

They are the father and the father-in-law

Of Gallia's bane: his

vicious life they know

And foul; thence comes the grief that rends

them thus.

"He, so robust of limb, who

measure keeps

In song, with him of feature prominent,

With ev'ry

virtue bore his girdle brac'd.

And if that stripling who behinds him

sits,

King after him had liv'd, his virtue then

From vessel to

like vessel had been pour'd;

Which may not of the other heirs be

said.

By James and Frederick his realms are held;

Neither the

better heritage obtains.

Rarely into the branches of the tree

Doth human worth mount up; and so ordains

He who bestows it, that as

his free gift

It may be call'd. To Charles my words apply

No less than to his brother in the song;

Which Pouille and Provence

now with grief confess.

So much that plant degenerates from its seed,

As more than Beatrice and Margaret

Costanza still boasts of her

valorous spouse.

"Behold the king of

simple life and plain,

Harry of England, sitting there alone:

He

through his branches better issue spreads.

"That

one, who on the ground beneath the rest

Sits lowest, yet his gaze

directs aloft,

Us William, that brave Marquis, for whose cause

The deed of Alexandria and his war

Makes Conferrat and Canavese

weep."

Now was the hour that wakens fond desire

In men at sea, and

melts their thoughtful heart,

Who in the morn have bid sweet friends

farewell,

And pilgrim newly on his road with love

Thrills, if he

hear the vesper bell from far,

That seems to mourn for the expiring

day:

When I, no longer taking heed to hear

Began, with wonder,

from those spirits to mark

One risen from its seat, which with its

hand

Audience implor'd. Both palms it join'd and rais'd,

Fixing

its steadfast gaze towards the east,

As telling God, "I care for

naught beside."

"Te Lucis Ante," so

devoutly then

Came from its lip, and in so soft a strain,

That

all my sense in ravishment was lost.

And the rest after, softly and

devout,

Follow'd through all the hymn, with upward gaze

Directed

to the bright supernal wheels.

Here,

reader! for the truth makes thine eyes keen:

For of so subtle texture

is this veil,

That thou with ease mayst pass it through unmark'd.

I saw that gentle band silently next

Look up, as if in expectation held,

Pale and in lowly guise; and from

on high

I saw forth issuing descend beneath

Two angels with two

flame-illumin'd swords,

Broken and mutilated at their points.

Green as the tender leaves but newly born,

Their vesture was, the

which by wings as green

Beaten, they drew behind them, fann'd in air.

A little over us one took his stand,

The other lighted on the'

Opposing hill,

So that the troop were in the midst contain'd.

Well I descried the whiteness on their

heads;

But in their visages the dazzled eye

Was lost, as faculty

that by too much

Is overpower'd. "From Mary's bosom both

Are come," exclaim'd Sordello, "as a guard

Over the vale, ganst him,

who hither tends,

The serpent." Whence, not knowing by which

path

He came, I turn'd me round, and closely press'd,

All

frozen, to my leader's trusted side.

Sordello

paus'd not: "To the valley now

(For it is time) let us descend; and

hold

Converse with those great shadows: haply much

Their sight

may please ye." Only three steps down

Methinks I measur'd, ere

I was beneath,

And noted one who look'd as with desire

To know

me. Time was now that air arrow dim;

Yet not so dim, that

'twixt his eyes and mine

It clear'd not up what was conceal'd before.

Mutually tow'rds each other we advanc'd.

Nino, thou courteous judge!

what joy I felt,

When I perceiv'd thou wert not with the bad!

No salutation kind on either part

Was

left unsaid. He then inquir'd: "How long

Since thou arrived'st

at the mountain's foot,

Over the distant waves?"—"O!" answer'd

I,

"Through the sad seats of woe this morn I came,

And still in

my first life, thus journeying on,

The other strive to gain." Soon

as they heard

My words, he and Sordello backward drew,

As

suddenly amaz'd. To Virgil one,

The other to a spirit turn'd,

who near

Was seated, crying: "Conrad! up with speed:

Come, see

what of his grace high God hath will'd."

Then turning round to me:

"By that rare mark

Of honour which thou ow'st to him, who hides

So deeply his first cause, it hath no ford,

When thou shalt be beyond

the vast of waves.

Tell my Giovanna, that for me she call

There,

where reply to innocence is made.

Her mother, I believe, loves me no

more;

Since she has chang'd the white and wimpled folds,

Which

she is doom'd once more with grief to wish.

By her it easily may be

perceiv'd,

How long in women lasts the flame of love,

If sight

and touch do not relume it oft.

For her so fair a burial will not

make

The viper which calls Milan to the field,

As had been made

by shrill Gallura's bird."

He spoke,

and in his visage took the stamp

Of that right seal, which with due

temperature

Glows in the bosom. My insatiate eyes

Meanwhile to heav'n had travel'd, even there

Where the bright stars

are slowest, as a wheel

Nearest the axle; when my guide inquir'd:

"What there aloft, my son, has caught thy gaze?"

I

answer'd: "The three torches, with which here

The pole is all on

fire." He then to me:

"The four resplendent stars, thou saw'st

this morn

Are there beneath, and these ris'n in their stead."

While yet he spoke. Sordello to

himself

Drew him, and cry'd: "Lo there our enemy!"

And with his

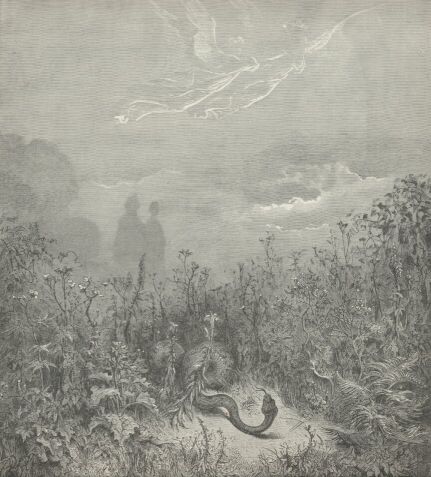

hand pointed that way to look.

Along

the side, where barrier none arose

Around the little vale, a serpent

lay,

Such haply as gave Eve the bitter food.

Between the grass

and flowers, the evil snake

Came on, reverting oft his lifted head;

And, as a beast that smoothes its polish'd coat,

Licking his hack.

I saw not, nor can tell,

How those celestial falcons from their

seat

Mov'd, but in motion each one well descried,

Hearing the

air cut by their verdant plumes.

The serpent fled; and to their

stations back

The angels up return'd with equal flight.

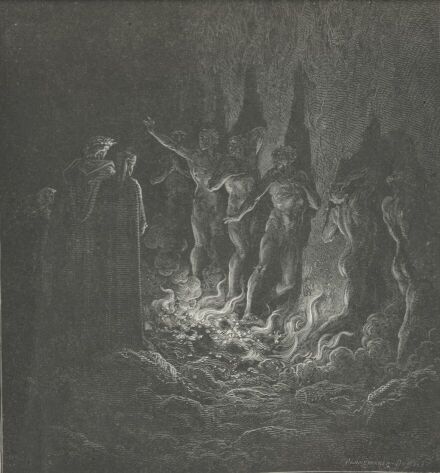

ENLARGE TO FULL SIZE

The Spirit (who to

Nino, when he call'd,

Had come), from viewing me with fixed ken,

Through all that conflict, loosen'd not his sight.

"So

may the lamp, which leads thee up on high,

Find, in thy destin'd lot,

of wax so much,

As may suffice thee to the enamel's height."

It

thus began: "If any certain news

Of Valdimagra and the neighbour part

Thou know'st, tell me, who once was mighty there

They call'd me

Conrad Malaspina, not

That old one, but from him I sprang. The

love

I bore my people is now here refin'd."

"In

your dominions," I answer'd, "ne'er was I.

But through all Europe

where do those men dwell,

To whom their glory is not manifest?

The fame, that honours your illustrious house,

Proclaims the nobles

and proclaims the land;

So that he knows it who was never there.

I swear to you, so may my upward route

Prosper! your honour'd nation

not impairs

The value of her coffer and her sword.

Nature and

use give her such privilege,

That while the world is twisted from his

course

By a bad head, she only walks aright,

And has the evil

way in scorn." He then:

"Now pass thee on: sev'n times the

tired sun

Revisits not the couch, which with four feet

The

forked Aries covers, ere that kind

Opinion shall be nail'd into thy

brain

With stronger nails than other's speech can drive,

If the

sure course of judgment be not stay'd."

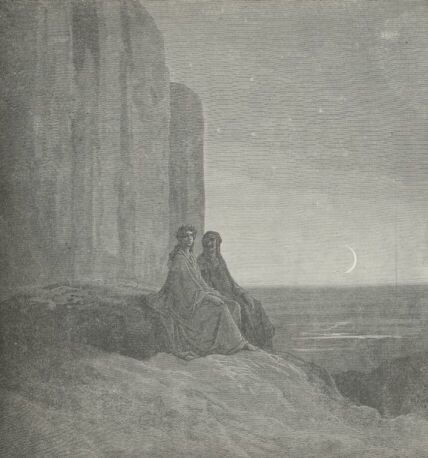

Now the fair consort of Tithonus old,

Arisen

from her mate's beloved arms,

Look'd palely o'er the eastern cliff:

her brow,

Lucent with jewels, glitter'd, set in sign

Of that

chill animal, who with his train

Smites fearful nations: and where

then we were,

Two steps of her ascent the night had past,

And

now the third was closing up its wing,

When I, who had so much of

Adam with me,

Sank down upon the grass, o'ercome with sleep,

There where all five were seated. In that hour,

When near the

dawn the swallow her sad lay,

Rememb'ring haply ancient grief,

renews,

And with our minds more wand'rers from the flesh,

And

less by thought restrain'd are, as 't were, full

Of holy divination

in their dreams,

Then in a vision did I seem to view

A

golden-feather'd eagle in the sky,

With open wings, and hov'ring for

descent,

And I was in that place, methought, from whence

Young

Ganymede, from his associates 'reft,

Was snatch'd aloft to the high

consistory.

"Perhaps," thought I within me, "here alone

He

strikes his quarry, and elsewhere disdains

To pounce upon the prey."

Therewith, it seem'd,

A little wheeling in his airy tour

Terrible as the lightning rush'd he down,

And snatch'd me upward even

to the fire.

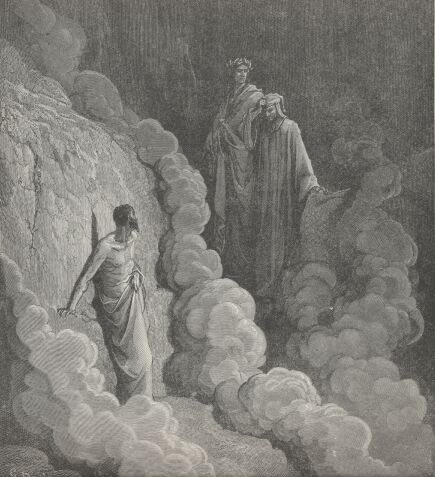

ENLARGE

TO FULL SIZE

There both, I thought, the eagle and myself

Did

burn; and so intense th' imagin'd flames,

That needs my sleep was

broken off. As erst

Achilles shook himself, and round him

roll'd

His waken'd eyeballs wond'ring where he was,

Whenas his

mother had from Chiron fled

To Scyros, with him sleeping in her arms;

E'en thus I shook me, soon as from my face

The slumber parted,

turning deadly pale,

Like one ice-struck with dread. Solo at my

side

My comfort stood: and the bright sun was now

More than two

hours aloft: and to the sea

My looks were turn'd. "Fear not,"

my master cried,

"Assur'd we are at happy point. Thy strength

Shrink not, but rise dilated. Thou art come

To Purgatory now.

Lo! there the cliff

That circling bounds it! Lo! the

entrance there,

Where it doth seem disparted! Ere the dawn

Usher'd the daylight, when thy wearied soul

Slept in thee, o'er the

flowery vale beneath

A lady came, and thus bespake me: I

Am

Lucia. Suffer me to take this man,

Who slumbers. Easier

so his way shall speed."

Sordello and the other gentle shapes

Tarrying, she bare thee up: and, as day shone,

This summit reach'd:

and I pursued her steps.

Here did she place thee. First her

lovely eyes

That open entrance show'd me; then at once

She

vanish'd with thy sleep." Like one, whose doubts

Are chas'd by

certainty, and terror turn'd

To comfort on discovery of the truth,

Such was the change in me: and as my guide

Beheld me fearless, up

along the cliff

He mov'd, and I behind him, towards the height.

Reader! thou markest how my theme doth rise,

Nor wonder therefore, if more artfully

I prop the structure! Nearer

now we drew,

Arriv'd' whence in that part, where first a breach

As of a wall appear'd, I could descry

A portal, and three steps

beneath, that led

For inlet there, of different colour each,

And

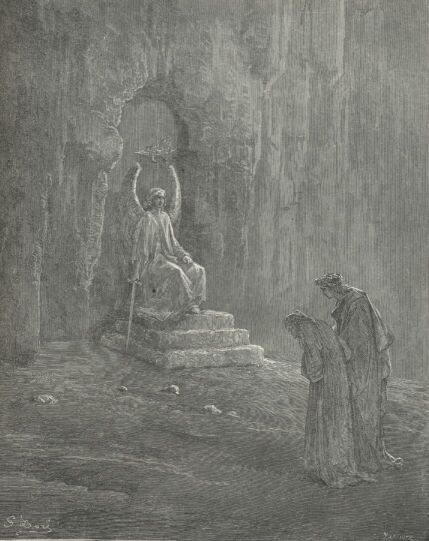

one who watch'd, but spake not yet a word.

As more and more mine eye

did stretch its view,

I mark'd him seated on the highest step,

In visage such, as past my power to bear.

ENLARGE TO FULL SIZE

Grasp'd in his hand a naked sword, glanc'd back

The rays so toward me, that I oft in vain

My sight directed. "Speak

from whence ye stand:"

He cried: "What would ye? Where is your

escort?

Take heed your coming upward harm ye not."

"A

heavenly dame, not skilless of these things,"

Replied the'

instructor, "told us, even now,

'Pass that way: here the gate is."—"And

may she

Befriending prosper your ascent," resum'd

The courteous

keeper of the gate: "Come then

Before our steps." We

straightway thither came.

The lowest

stair was marble white so smooth

And polish'd, that therein my

mirror'd form

Distinct I saw. The next of hue more dark

Than sablest grain, a rough and singed block,

Crack'd lengthwise and

across. The third, that lay

Massy above, seem'd porphyry, that

flam'd

Red as the life-blood spouting from a vein.

On this God's

angel either foot sustain'd,

Upon the threshold seated, which

appear'd

A rock of diamond. Up the trinal steps

My leader

cheerily drew me. "Ask," said he,

"With

humble heart, that he unbar the bolt."

Piously

at his holy feet devolv'd

I cast me, praying him for pity's sake

That he would open to me: but first fell

Thrice on my bosom

prostrate. Seven times

The letter, that denotes the inward

stain,

He on my forehead with the blunted point

Of his drawn

sword inscrib'd. And "Look," he cried,

"When enter'd, that thou

wash these scars away."

Ashes, or earth

ta'en dry out of the ground,

Were of one colour with the robe he

wore.

From underneath that vestment forth he drew

Two keys of

metal twain: the one was gold,

Its fellow silver. With the

pallid first,

And next the burnish'd, he so ply'd the gate,

As

to content me well. "Whenever one

Faileth of these, that in the

keyhole straight

It turn not, to this alley then expect

Access

in vain." Such were the words he spake.

"One is more precious:

but the other needs

Skill and sagacity, large share of each,

Ere

its good task to disengage the knot

Be worthily perform'd. From

Peter these

I hold, of him instructed, that I err

Rather in

opening than in keeping fast;

So but the suppliant at my feet

implore."

Then of that hallow'd gate he

thrust the door,

Exclaiming, "Enter, but this warning hear:

He

forth again departs who looks behind."

As

in the hinges of that sacred ward

The swivels turn'd, sonorous metal

strong,

Harsh was the grating; nor so surlily

Roar'd the

Tarpeian, when by force bereft

Of good Metellus, thenceforth from his

loss

To leanness doom'd. Attentively I turn'd,

List'ning

the thunder, that first issued forth;

And "We praise thee, O God,"

methought I heard

In accents blended with sweet melody.

The

strains came o'er mine ear, e'en as the sound

Of choral voices, that

in solemn chant

With organ mingle, and, now high and clear,

Come

swelling, now float indistinct away.

When we had passed the threshold of the gate

(Which the soul's

ill affection doth disuse,

Making the crooked seem the straighter

path),

I heard its closing sound. Had mine eyes turn'd,

For that offence what plea might have avail'd?

We

mounted up the riven rock, that wound

On either side alternate, as

the wave

Flies and advances. "Here some little art

Behooves us," said my leader, "that our steps

Observe the varying

flexure of the path."

Thus we so slowly

sped, that with cleft orb

The moon once more o'erhangs her wat'ry

couch,

Ere we that strait have threaded. But when free

We

came and open, where the mount above

One solid mass retires, I spent,

with toil,

And both, uncertain of the way, we stood,

Upon a

plain more lonesome, than the roads

That traverse desert wilds.

From whence the brink

Borders upon vacuity, to foot

Of the

steep bank, that rises still, the space

Had measur'd thrice the

stature of a man:

And, distant as mine eye could wing its flight,

To leftward now and now to right dispatch'd,

That cornice equal in

extent appear'd.

Not yet our feet had

on that summit mov'd,

When I discover'd that the bank around,

Whose proud uprising all ascent denied,

Was marble white, and so

exactly wrought

With quaintest sculpture, that not there alone

Had Polycletus, but e'en nature's self

Been sham'd. The angel

who came down to earth

With tidings of the peace so many years

Wept for in vain, that op'd the heavenly gates

From their long

interdict before us seem'd,

In a sweet act, so sculptur'd to the

life,

He look'd no silent image. One had sworn

He had said,

"Hail!" for she was imag'd there,

By whom the key did open to God's

love,

And in her act as sensibly impress

That word, "Behold the

handmaid of the Lord,"

As figure seal'd on wax. "Fix not thy

mind

On one place only," said the guide belov'd,

Who had me near

him on that part where lies

The heart of man. My sight

forthwith I turn'd

And mark'd, behind the virgin mother's form,

Upon that side, where he, that mov'd me, stood,

Another story graven

on the rock.

I passed athwart the bard,

and drew me near,

That it might stand more aptly for my view.

There in the self-same marble were engrav'd

The cart and kine,

drawing the sacred ark,

That from unbidden office awes mankind.

Before it came much people; and the whole

Parted in seven quires.

One sense cried, "Nay,"

Another, "Yes, they sing." Like

doubt arose

Betwixt the eye and smell, from the curl'd fume

Of

incense breathing up the well-wrought toil.

Preceding the blest

vessel, onward came

With light dance leaping, girt in humble guise,

Sweet Israel's harper: in that hap he seem'd

Less and yet more than

kingly. Opposite,

At a great palace, from the lattice forth

Look'd Michol, like a lady full of scorn

And sorrow. To behold

the tablet next,

Which at the hack of Michol whitely shone,

I

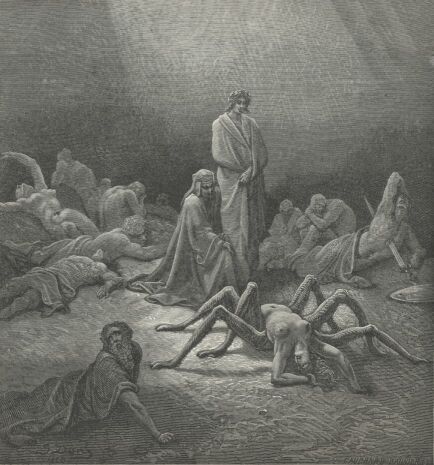

mov'd me. There was storied on the rock

The' exalted glory of

the Roman prince,

Whose mighty worth mov'd Gregory to earn

His

mighty conquest, Trajan th' Emperor.

A widow at his bridle stood,

attir'd

In tears and mourning. Round about them troop'd

Full throng of knights, and overhead in gold

The eagles floated,

struggling with the wind.

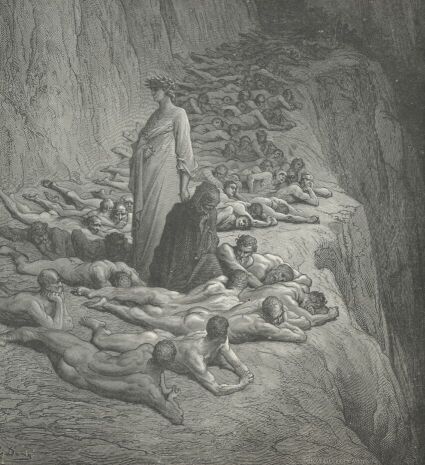

ENLARGE TO FULL SIZE

The wretch appear'd amid all these to say:

"Grant vengeance, sire! for, woe beshrew this heart

My son is

murder'd." He replying seem'd;

"Wait

now till I return." And she, as one

Made hasty by her grief; "O sire,

if thou

Dost not return?"—"Where I am, who then is,

May

right thee."—"What to thee is other's good,

If thou neglect thy

own?"—"Now comfort thee,"

At length he answers. "It

beseemeth well

My duty be perform'd, ere I move hence:

So

justice wills; and pity bids me stay."

He,

whose ken nothing new surveys, produc'd

That visible speaking, new to

us and strange

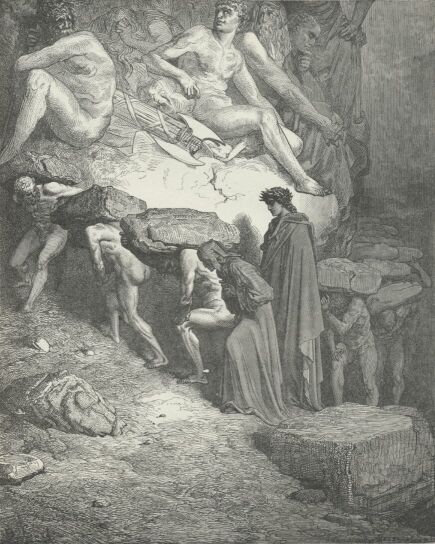

The like not found on earth. Fondly I gaz'd

Upon those patterns of meek humbleness,

Shapes yet more precious for

their artist's sake,

When "Lo," the poet whisper'd, "where this way

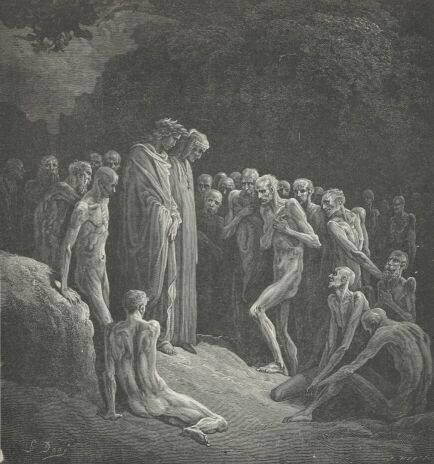

(But slack their pace), a multitude advance.

These to the lofty steps

shall guide us on."

Mine eyes, though

bent on view of novel sights

Their lov'd allurement, were not slow to

turn.

Reader! I would not that amaz'd

thou miss

Of thy good purpose, hearing how just God

Decrees our

debts be cancel'd. Ponder not

The form of suff'ring. Think

on what succeeds,

Think that at worst beyond the mighty doom

It

cannot pass. "Instructor," I began,

"What I see hither tending,

bears no trace

Of human semblance, nor of aught beside

That my

foil'd sight can guess." He answering thus:

"So courb'd to

earth, beneath their heavy teems

Of torment stoop they, that mine eye

at first

Struggled as thine. But look intently thither,

An

disentangle with thy lab'ring view,

What underneath those stones

approacheth: now,

E'en now, mayst thou discern the pangs of each."

Christians and proud! O poor and wretched

ones!

That feeble in the mind's eye, lean your trust

Upon

unstaid perverseness! Know ye not

That we are worms, yet made at last

to form

The winged insect, imp'd with angel plumes

That to

heaven's justice unobstructed soars?

Why buoy ye up aloft your

unfleg'd souls?

Abortive then and shapeless ye remain,

Like the

untimely embryon of a worm!

As, to

support incumbent floor or roof,

For corbel is a figure sometimes

seen,

That crumples up its knees unto its breast,

With the

feign'd posture stirring ruth unfeign'd

In the beholder's fancy; so I

saw

These fashion'd, when I noted well their guise.

Each,

as his back was laden, came indeed

Or more or less contract; but it

appear'd

As he, who show'd most patience in his look,

Wailing

exclaim'd: "I can endure no more."

"O thou Almighty Father, who dost make

The heavens thy

dwelling, not in bounds confin'd,

But that with love intenser there

thou view'st

Thy primal effluence, hallow'd be thy name:

Join

each created being to extol

Thy might, for worthy humblest thanks and

praise

Is thy blest Spirit. May thy kingdom's peace

Come

unto us; for we, unless it come,

With all our striving thither tend

in vain.

As of their will the angels unto thee

Tender meet

sacrifice, circling thy throne

With loud hosannas, so of theirs be

done

By saintly men on earth. Grant us this day

Our daily

manna, without which he roams

Through this rough desert retrograde,

who most

Toils to advance his steps. As we to each

Pardon

the evil done us, pardon thou

Benign, and of our merit take no count.

'Gainst the old adversary prove thou not

Our virtue easily subdu'd;

but free

From his incitements and defeat his wiles.

This last

petition, dearest Lord! is made

Not for ourselves, since that were

needless now,

But for their sakes who after us remain."

Thus

for themselves and us good speed imploring,

Those spirits went

beneath a weight like that

We sometimes feel in dreams, all, sore

beset,

But with unequal anguish, wearied all,

Round the first

circuit, purging as they go,

The world's gross darkness off: In our

behalf

If there vows still be offer'd, what can here

For them be

vow'd and done by such, whose wills

Have root of goodness in them?

Well beseems

That we should help them wash away the stains

They carried hence, that so made pure and light,

They may spring

upward to the starry spheres.

"Ah! so may mercy-temper'd

justice rid

Your burdens speedily, that ye have power

To stretch

your wing, which e'en to your desire

Shall lift you, as ye show us on

which hand

Toward the ladder leads the shortest way.

And if

there be more passages than one,

Instruct us of that easiest to

ascend;

For this man who comes with me, and bears yet

The charge

of fleshly raiment Adam left him,

Despite his better will but slowly

mounts."

From whom the answer came unto these words,

Which my

guide spake, appear'd not; but 'twas said.

"Along the bank to

rightward come with us,

And ye shall find a pass that mocks not toil

Of living man to climb: and were it not

That I am hinder'd by the

rock, wherewith

This arrogant neck is tam'd, whence needs I stoop

My visage to the ground, him, who yet lives,

Whose name thou speak'st

not him I fain would view.

To mark if e'er I knew him? and to

crave

His pity for the fardel that I bear.

I was of Latiun,

of a Tuscan horn

A mighty one: Aldobranlesco's name

My

sire's, I know not if ye e'er have heard.

My old blood and

forefathers' gallant deeds

Made me so haughty, that I clean forgot

The common mother, and to such excess,

Wax'd in my scorn of all men,

that I fell,

Fell therefore; by what fate Sienna's sons,

Each

child in Campagnatico, can tell.

I am Omberto; not me only pride

Hath injur'd, but my kindred all involv'd

In mischief with her.

Here my lot ordains

Under this weight to groan, till I appease

God's angry justice, since I did it not

Amongst the living, here

amongst the dead."

List'ning I bent my visage down: and one

(Not he who spake) twisted beneath the weight

That urg'd him, saw me,

knew me straight, and call'd,

Holding his eyes With difficulty fix'd

Intent upon me, stooping as I went

Companion of their way. "O!"

I exclaim'd,

"Art thou not Oderigi, art not thou

Agobbio's glory, glory of that art

Which they of Paris call the

limmer's skill?"

"Brother!" said he, "with tints that gayer

smile,

Bolognian Franco's pencil lines the leaves.

His all the

honour now; mine borrow'd light.

In truth I had not been thus

courteous to him,

The whilst I liv'd, through eagerness of zeal

For that pre-eminence my heart was bent on.

Here of such pride the

forfeiture is paid.

Nor were I even here; if, able still

To sin,

I had not turn'd me unto God.

O powers of man! how vain your

glory, nipp'd

E'en in its height of verdure, if an age

Less

bright succeed not! Cimabue thought

To lord it over painting's

field; and now

The cry is Giotto's, and his name eclips'd.

Thus

hath one Guido from the other snatch'd

The letter'd prize: and he

perhaps is born,

Who shall drive either from their nest. The

noise

Of worldly fame is but a blast of wind,

That blows from

divers points, and shifts its name

Shifting the point it blows from.

Shalt thou more

Live in the mouths of mankind, if thy flesh

Part shrivel'd from thee, than if thou hadst died,

Before the coral

and the pap were left,

Or ere some thousand years have passed? and

that

Is, to eternity compar'd, a space,

Briefer than is the

twinkling of an eye

To the heaven's slowest orb. He there who

treads

So leisurely before me, far and wide

Through Tuscany